Toilets as opportunities?

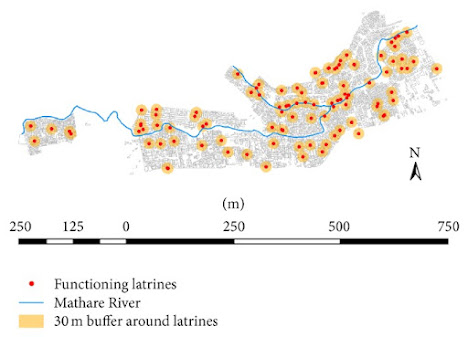

My last blog will be continuing on the theme of toilets – offering some hope for the future of toilets in informal settlements in the global south. The film Slumdog Millionaire perfectly captured the paradox of slum life – the harsh conditions that people are living in, but also the potential of entrepreneurialism to generate income. This paradox is also seen in Mathare, an informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya (as shown in Figure 1). Figure 1: Alleyway in a slum in Mathare, Nairobi In Mathare, the toilet is being reinvented – not just on a public health imperative, but as a business opportunity (‘A toilet is not just a toilet’). At ‘Number 10’ neighbourhood, a shared toilet (which has a fee to use) is managed by a local youth group , generating income for themselves as well as other avenues – such as a mobile banking kiosk and water point, which are next to the toilet. In this way, urban sanitation is linked to urban economies and infrastructures. Ikotoilet (as ...