'A toilet is not just a toilet'

This blog will delve further ‘into’ something that I have touched on in my other blogs – the toilet – of which discussions of sanitation have been mobilised around. While I was watching Slumdog Millionaire, I started to understand the scale of the sanitation crisis in informal settlements in the global south. From the hanging latrines – which can pollute waterways and often require payment, to open defecation, which thousands of slum residents have to navigate every day. In this setting, a toilet is a symbol of vulnerability and urban precarity.

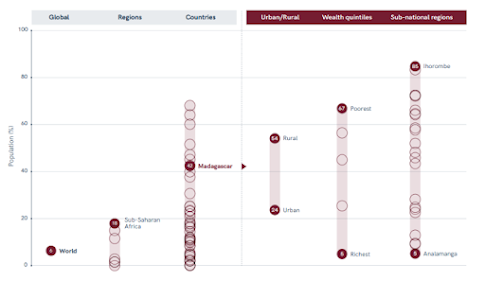

In

2020, 3.6 billion people lacked safely managed

sanitation, including 494 million practicing open defecation. As Figure 1 shows,

Sub-Saharan Africa has higher rates of open defecation, compared to the rest of

the world, and Madagascar has huge inequalities in the levels of open

defecation within the country – from rural to poor areas, richer to poorer. Not

only should the elimination of open defecation focus on the poorest and rural

areas, but health interventions should aim to close the rich-poor gap in open

defecation rates,

which could be done, for example, by subsidies to the poor.

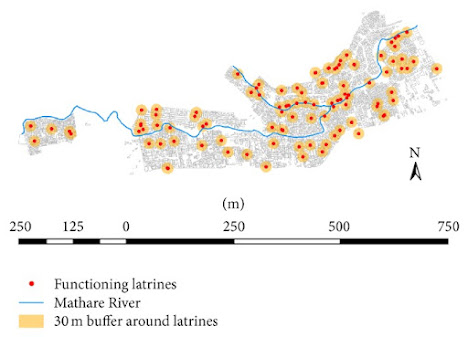

Community toilets often are in poor conditions and offer little privacy or dignity – as seen in Figure 2. Therefore, residents are forced to improvise – through open defecation or flying toilets. This creates a public health risk of the spread of disease, mainly through the contamination of drinking water. Especially in densely populated urban areas, where pit latrines and septic tanks are close to water sources from shallow aquifers. Therefore, central to slum upgrading is the provision of safe water and sanitation.

Figure 2: Typical toilet in Mathare

“A toilet is not just a toilet—it’s a

lifesaver, dignity-protector and opportunity-maker,”. This is because of the

toilets wider impact – driving improvements in health, gender equality,

education, economics, and the environment. A safe toilet ensures the separation of

excreta from human contact and groundwater – fundamental to the health of

people. A toilet gives girls dignity and safety so that they can go to school

and fully participate in society (the lack of toilet represents gendered insecurity, where women are

most vulnerable).

In this way, sanitation plays a critical role in efforts to eradicate

poverty.

Therefore, the 19th of November marks World Toilet Day, bringing

attention to the global sanitation crisis and calling on people to ‘give a

shit’. Adverts are mobilising children as key to ending toilet taboos – as seen

in Figure 3.

Figure

3: Advert from World Toilet Day 2019 –

‘This is not just a toilet’.

There

is a shocking paradox of modernity; more people have access to a mobile phone (87%) than

access to a safe toilet (63%). This highlights the uneven and

segregated service provision as well as the absentee state. A toilet is not

just a toilet – it represents more than just sanitation challenges – but

challenges over having a ‘right to the city’. Where the state does not provide

basic services, there are questions such as; who is a citizen?

The

toilet is a humanitarian, public health,

educational, urban planning, technological and business concern that requires cooperation

from a number of stakeholders if SDG 6 is to be met.

Comments

Post a Comment